-

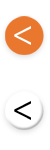

The 1950s ushered in a diversity of fresh and bold artistic styles on both sides of the Atlantic. From the avant-garde movements Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel to artist groups Cobra and Dau al Set, the revitalization of experimental art following World War II signified a renewed interest in freedom of expression, spontaneity, and unorthodox materials. French art critic Michel Tapié enthusiastically declared the existence of un art autre (art of another kind)—a radical break with all traditional notions of order and composition in a movement toward something wholly "other." Drawn from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum collection, this presentation seeks to consider a decade of vanguard activity and bring greater attention to some lesser-known pioneers alongside those long since canonized.

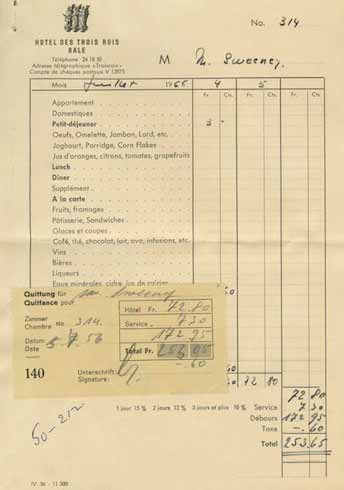

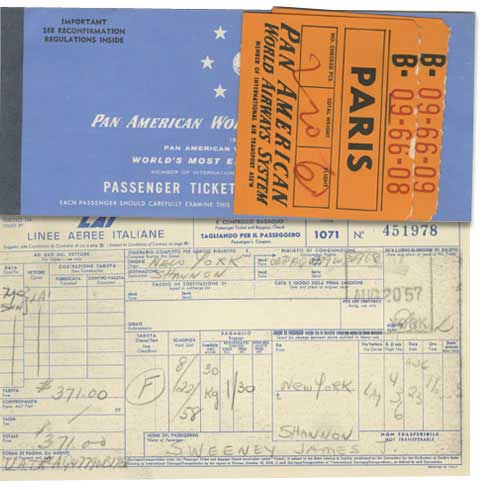

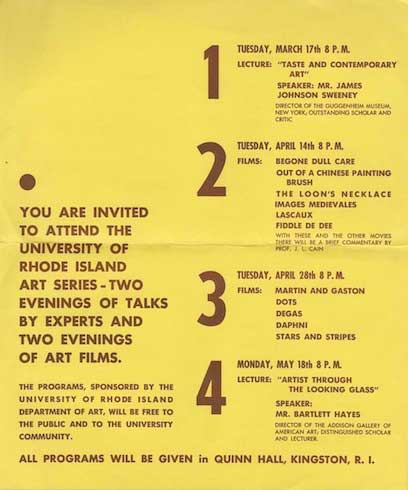

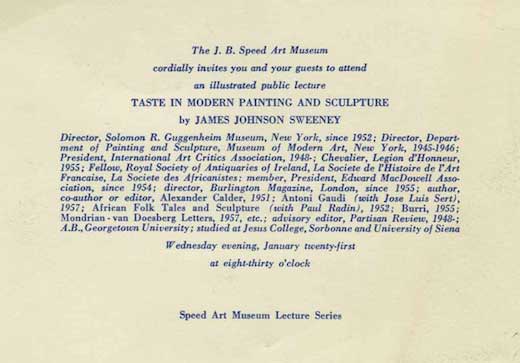

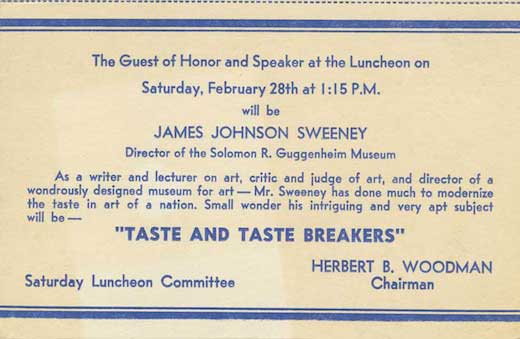

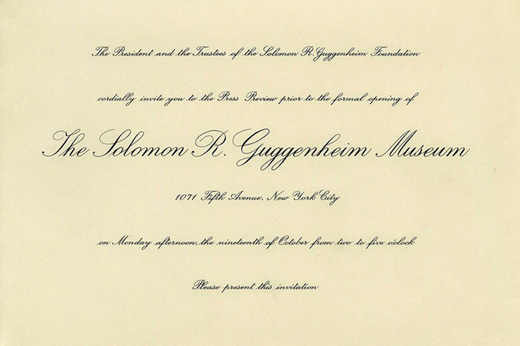

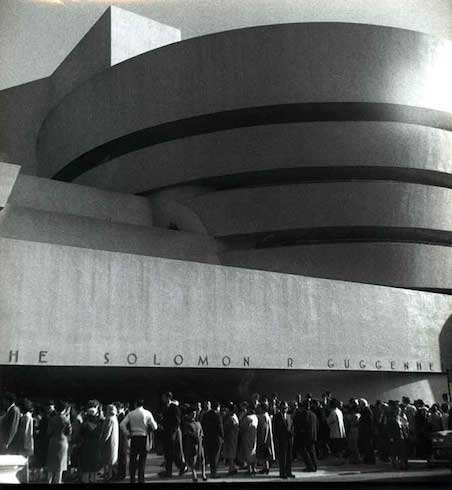

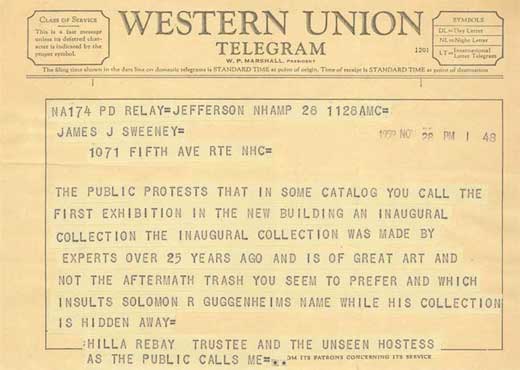

Art of Another Kind likewise celebrates a vital moment in the Guggenheim's history. Following Solomon R. Guggenheim's death in 1949 and the departure of founding director and curator Hilla Rebay in 1952, the museum's second director, James Johnson Sweeney, championed emerging avant-garde artists whom he called the "tastebreakers" of his day, the individuals who "break open and enlarge our artistic frontiers." The robust addition to the collection of contemporary painting and sculpture dating from the 1950s attests to Sweeney's commitment to the innovative art of his time, continuing the long-standing mission of the museum's founders. The current presentation features both those works presciently acquired in the 1950s—many of which were on display at the 1959 inaugural exhibition of the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed building—and those added to the Guggenheim's holdings through the present day.

This exhibition is organized by Tracey Bashkoff, Curator, Collections and Exhibitions, and Megan Fontanella, Assistant Curator, Collections and Provenance.

-

The Stories

Learn more about this radically changing art-historical landscape and the Guggenheim's unique contributions to the period through six stories and a selection of supporting materials from the museum's archives, including letters between artists and James Johnson Sweeney, exhibition invitations, and historic photographs of the art on view at the Guggenheim.

-

Mark Rothko, Untitled (Violet, Black, Orange, Yellow on White and Red), 1949 407500

With paintings such as Untitled (Violet, Black, Orange, Yellow on White and Red), Mark Rothko arrived at his mature idiom. For the next 20 years, he explored the expressive potential of stacked rectangular fields of luminous colors. Like other New York school artists, Rothko used abstract means to express universal human emotions, earnestly striving to create an art of awe-inspiring intensity for a secular world. For him the canvases enacted a violent battle of opposites—vertical versus horizontal, hot colors versus cold—invoking the existential conflicts of modernity. Often larger than a human being, Rothko's canvases inspire the kind of wonder and reverence traditionally associated with monumental religious or landscape painting.

-

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Volage, 1951 354500

Nearly ten years after Louise Bourgeois moved to New York from her native Paris, she embarked on a series of approximately 80 carved and assembled wooden sculptures known as Personnages (1945–55). These life-size, semiabstract, vaguely anthropomorphic sculptures functioned as surrogates for people close to her, and she described Femme Volage as a self-portrait. The Personnages have clear associations with avant-garde art of the late 1940s, particularly in their totemlike structures, which can be read as a three-dimensional correlate to the totemic forms in the early work of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Seventeen of these Personnages were featured in a solo exhibition at New York's Peridot Gallery in 1949. The thin, freestanding, vertical forms inhabited the room in small clusters like visitors conversing while perusing the exhibition.

-

Emilio Vedova, Image of Time (Barrier), 1951 647500

Emilio Vedova produced art in response to contemporary social upheavals, but his political position was contrary to that of his early modern counterparts, the Italian Futurists, who coalesced as a group in the years preceding World War I. While the Futurists romantically celebrated the aggressive energies of societal conflict and technological advancement, Vedova's feverish, violent canvases convey—in abstract terms—his horror and protest of man's assault on his own kind. Although the motivation behind Image of Time (Barrier) is political, the painting's formal preoccupations parallel those of the American Abstract Expressionists, especially Franz Kline. The drama of the angular, graphic slashes of black on white is heightened with accents of orange-red. Occupying a shallow space, pictorial elements are locked together in formal combat and emotional turmoil.

-

Georges Mathieu, Painting, 1952 675450

A key figure of the postwar art scene in Paris, as well as a champion—and competitor—of the burgeoning New York school of abstract painters, Georges Mathieu practiced a decidedly calligraphic mode of gestural abstraction. His paintings were executed with controlled force, resulting in a matrix of lines bursting from a single point and thrusting outward in every direction. The artist often squeezed paint directly from tubes onto the canvas and emphasized the necessity of rapid application in order to harness an intuitive expression. Mathieu also occasionally introduced a performative dimension to his painting in the 1950s, executing large canvases before audiences. This merger of painting and performance anticipated the work of Yves Klein and others in the late 1950s and 1960s.

-

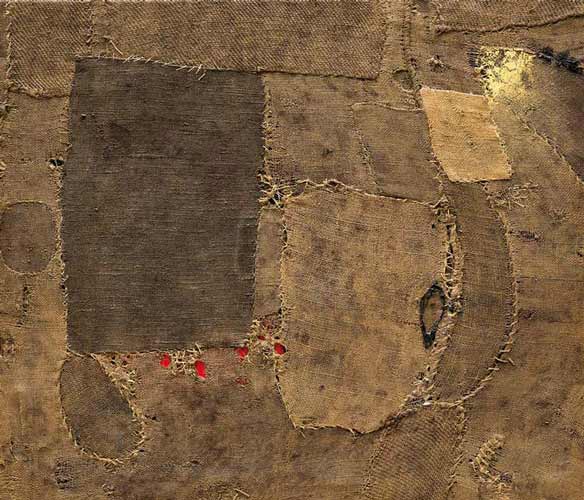

Alberto Burri, Composition, 1953 584500

While interred as a prisoner of war in Texas during World War II, Alberto Burri—then a doctor in the Italian army—took up painting and demonstrated an early predilection for cast-off, discarded materials. After his release, Burri fully dedicated himself to art making and embraced the inherent beauty of natural, ephemeral materials and unconventional mediums. From 1950 to 1960, Burri executed a series of textile constructions called sacchi (sacks) using paint and sewn or collaged pieces of burlap and fabric. Early commentators suggested that the patchwork surfaces of the sacchi signified living flesh violated during warfare. Burri, however, maintained that he chose his materials purely for their formal properties; titles like Composition emphasize his concern with notions of construction rather than metaphor.

-

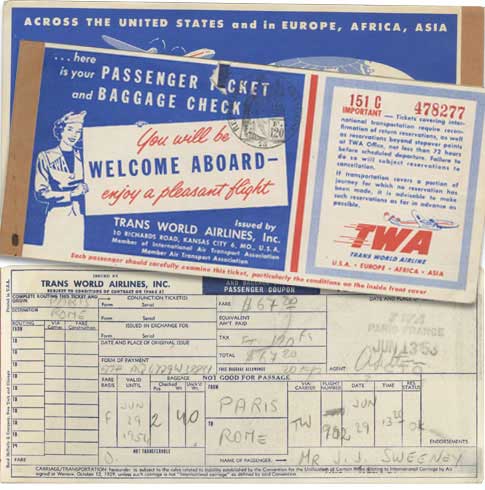

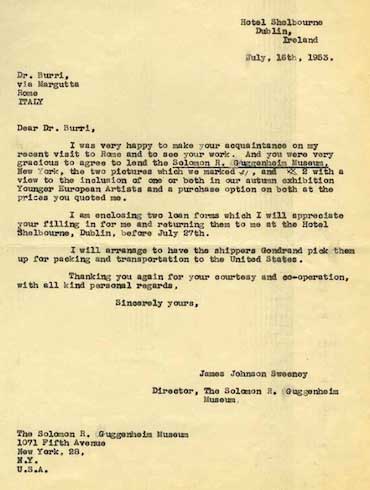

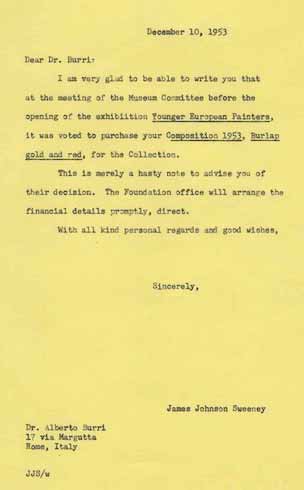

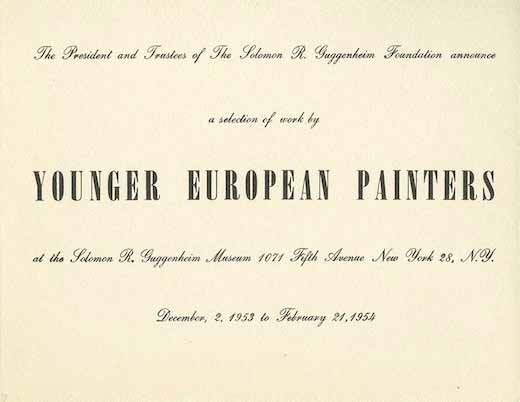

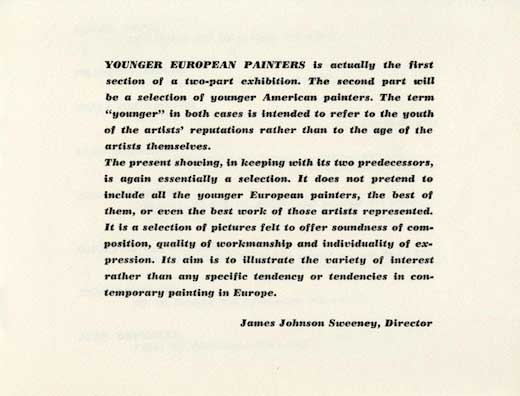

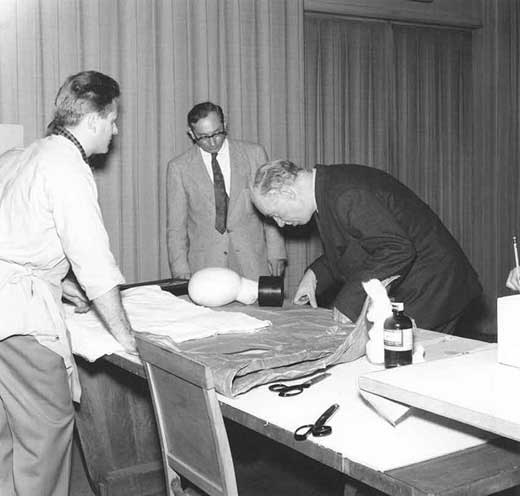

Younger European Painters at the Guggenheim in 1953

In 1953 and 1954, then–Guggenheim director James Johnson Sweeney staged complementary "younger painters" presentations at the museum's temporary location prior to the construction of the Frank Lloyd Wright building. Sweeney used this term to refer not to age, but to an artist's established reputation. He not only traveled extensively abroad to uncover the freshest art of his time, but he also secured key acquisitions through these exhibitions. Of the 32 works in the first show, Younger European Painters: A Selection (December 3, 1953–May 2, 1954), 26 entered the collection, including new works by Karel Appel, Alberto Burri, Hans Hartung, and Georges Mathieu.

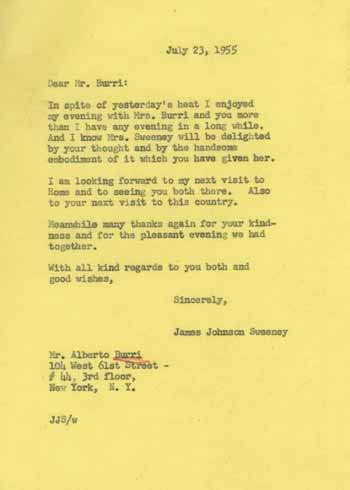

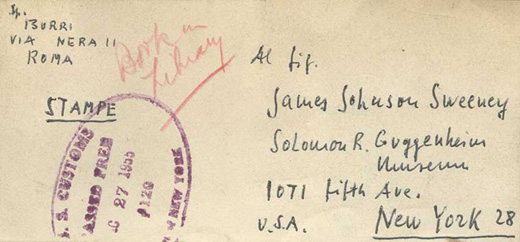

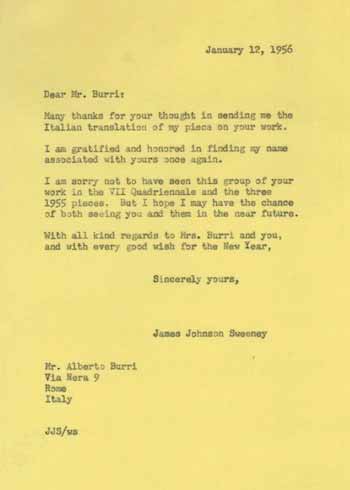

Sweeney visited Burri's studio in Rome to make a selection for the 1953 exhibition. Composition (1953), from Burri's series of textile constructions called sacchi (sacks), was purchased from the artist, who had by this time embraced the inherent beauty of natural, ephemeral materials and unconventional mediums. Early commentators suggested that the patchwork surfaces of the sacchi signified living flesh violated during warfare. Sweeney would continue supporting Burri's career, authoring a 1955 monograph and contributing a catalogue essay to Burri's presentation at the 1958 Venice Biennale.

Alberto Burri, Composition, 1953 Oil, gold paint, and glue on burlap and canvas, 86 x 100.4 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 53.1364. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Oil, gold paint, and glue on burlap and canvas, 86 x 100.4 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 53.1364. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

19content/video/YepYapFinal_microsite.mp4images/art/YepYap_posterframe.jpg475845

19content/video/YepYapFinal_microsite.mp4images/art/YepYap_posterframe.jpg475845

-

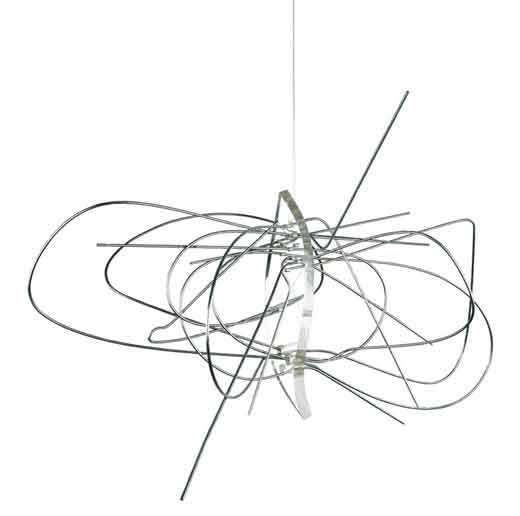

Eduardo Chillida, From Within, March 1953 355500

Eduardo Chillida began his career studying architecture; his oeuvre displays an underlying sense of structural organization and discipline in materials, planning of spatial relationships, and scaling of elements. A pride in craftsmanship, especially in the wrought iron work of the blacksmith, is a part of the artist's Basque heritage. From the early 1950s, his sculpture revealed the importance of the material, as seen in From Within, which exudes a vitality and tension in the bending and joining of iron elements. The curved and pointed shapes of iron bars create a silhouette that changes when seen from different angles. Skeletal forms are aligned in an open spatial organization around a central core; thus, the demarcation of space is based on an essentially linear structure.

-

Jackson Pollock, Ocean Greyness, 1953 700446

Jackson Pollock's first fully mature works—dating between 1942 and 1947—use an idiosyncratic iconography he developed in part as a response to Surrealism. Arising from this confluence of abstraction and figuration are Pollock's breakthrough works, commonly perceived as pure abstraction and made over the course of an explosive period between late 1947 and 1950 as represented by Ocean Greyness. In the postwar period, artists were anxiously aware of human irrationality and vulnerability; many, including Pollock, expressed their concerns in an abstract art that chronicled the ardor and exigencies of modern life. Pollock also broke free from the standard use of implements at this time, usually abandoning their direct contact with the surface. Working from above the picture plane, he dripped and poured enamel paints on canvases and papers, a method that more precisely controlled the application of line and introduced radical new directions in art.

-

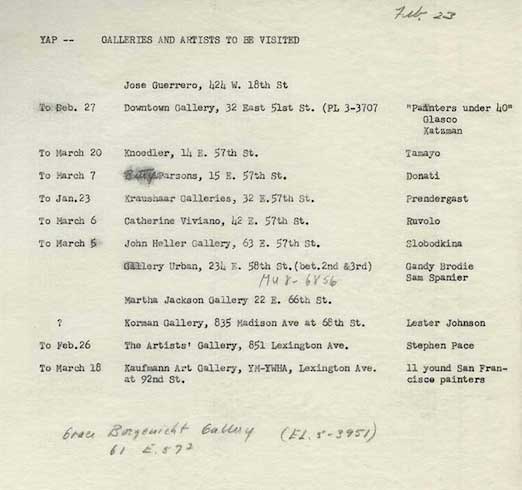

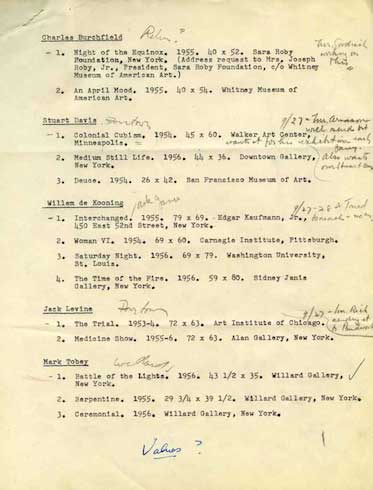

Younger American Painters at the Guggenheim in 1954

For Younger American Painters: A Selection (May 12–September 26, 1954), the companion show to Younger European Painters (1953–54), then–Guggenheim director James Johnson Sweeney embraced what he called "fresh, unfamiliar concepts of our own"—art by pioneering U.S.-based painters. The museum ultimately acquired 14 works on view, and the addition of paintings by Jimmy Ernst, Franz Kline, and Jackson Pollock (Ocean Greyness, 1953, at right), among others, marked the entry of these New York school artists to the museum's collection.

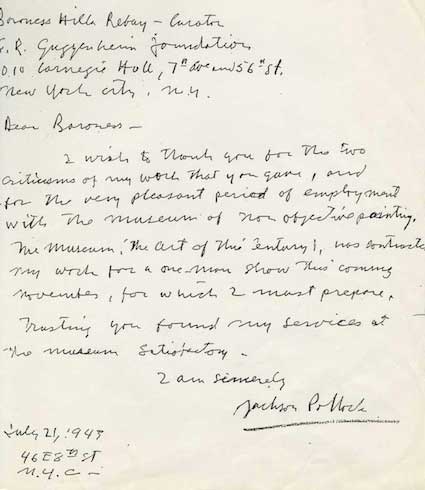

Pollock had briefly worked as a maintenance man at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (forerunner of the Guggenheim Museum) before Peggy Guggenheim offered him a contract with her gallery-museum Art of This Century, New York, beginning in July 1943. She supported Pollock with a monthly stipend and actively promoted and sold his paintings. Art of This Century hosted his first solo exhibition, in late 1943, with an introduction by Sweeney in the accompanying catalogue. After her return to Europe, Guggenheim also organized Pollock's first European solo exhibition, at the Museo Correr, Venice, in 1950.

Jackson Pollock, Ocean Greyness, 1953 Oil on canvas, 146.7 x 229 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 54.1408. © 2012 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Oil on canvas, 146.7 x 229 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 54.1408. © 2012 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

-

Willem de Kooning, Composition, 1955 437500

Although he is often cited as the originator of Action Painting, an abstract, purely formal and intuitive means of expression, Willem de Kooning most often worked from observing reality, primarily figures and the landscape. From 1950 to 1955, he completed his famous Women series, which integrated the human form with the aggressive paint application, bold colors, and sweeping strokes of Abstract Expressionism. Composition serves as a bridge between the Women and his subsequent series of urban and rural landscapes. Indeed, the work reads as a Woman obfuscated by the artist's agitated brushwork, clashing colors, and allover composition. Completed while the artist had a studio in downtown New York, Composition is energized by dashes of red, turquoise, and chrome yellow that suggest the frenetic pace of city life.

-

Karel Appel, The Crying Crocodile Tries to Catch the Sun, 1956 294385

Karel Appel was a founding member of Cobra, a European artists' group that emphasized material and its spontaneous application. Appel often rendered his human or animal figures in a deliberately awkward, naive way, with no attempt at modeling or perspectival illusionism. The crocodile in this canvas is presented as a flat and immobile form, contoured with heavy black lines in the manner of a child's drawing. The physicality of the thick application of paint and the boldness and brutality of Appel's brushwork increase the emotional intensity of his violent color contrasts. In 1956 the artist summarized the genesis of his work: "I never try to make a painting; it is a howl, it is naked, it is like a child, it is a caged tiger. . . . My tube is like a rocket writing its own space."

-

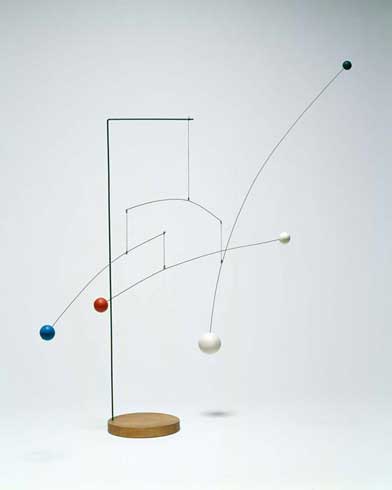

Alexander Calder, Red Lily Pads, 1956 643500

While living in Paris from 1926 to 1933, Alexander Calder had increasing contact with the European avant-garde. On seeing Calder's motorized sculptures in the fall of 1931, Marcel Duchamp dubbed them mobile, as he had his own motorized work decades earlier. Calder embraced the meanings implied by the French term, referring both to a motive and to something movable, even quick and unstable. In the late 1930s, Calder began to favor forms that suggested plants and animals over galactic subjects. Like the Surrealists he often exhibited alongside, Calder had an affinity for biomorphic forms and accidental relationships. He continued to reference the natural world in his work throughout his life, as in the monumental Red Lily Pads. Its ovoid disks float parallel to the earth in fleeting arrangements, like leaves skimming the surface of water.

-

Expanding the Sculpture Collection

In his first director's report to the board of trustees, James Johnson Sweeney prioritized, among other things, addressing the gap in the collection pertaining to sculpture. Finding it too earthbound to communicate spiritually, founding director Hilla Rebay had not actively collected sculpture, save for a few examples by Alexander Calder, Claire Falkenstein, Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy, and others.

From early modernism, Sweeney added nine sculptures by Constantin Brancusi by 1958, creating a concentration of his work for the museum. Sweeney also acquired works by Jean Arp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Lipchitz, Amedeo Modigliani, and others. Five 1930s and 1940s Calder works were gifted from a major collector, though Sweeney had been Calder's close friend since they had met in Paris in the 1930s. Sweeney also collected mid-century sculpture, including works by Eduardo Chillida, Pietro Consagra, and Theodore Roszak. After Sweeney's departure in 1960, the museum remained committed to this medium. Calder's Red Lily Pads (1956) was acquired during his major retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1964–65.

Alexander Calder, Red Lily Pads, 1956 Painted sheet metal and metal rods, 106.7 x 510.5 x 276.9 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 65.1737. © 2012 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Painted sheet metal and metal rods, 106.7 x 510.5 x 276.9 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 65.1737. © 2012 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

35content/video/Chillida_credits.mp4images/art/Chillida_posterframe.jpg475845

35content/video/Chillida_credits.mp4images/art/Chillida_posterframe.jpg475845

-

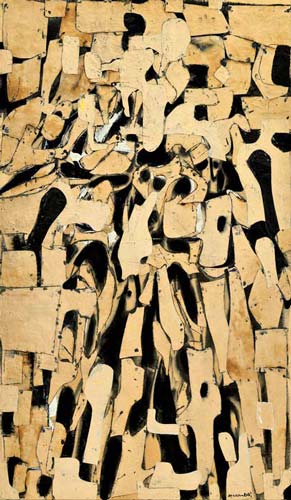

Conrad Marca-Relli, Warrior, 1956 291500

Conrad Marca-Relli entered the vibrant New York art scene in the late 1940s, joining those working downtown in the vicinity of Greenwich Village and becoming a founding member of the Club, an informal assembly of avant-garde artists. While visiting Mexico in 1953, Marca-Relli ran out of paint and soon began experimenting with collage, creating essentially pictorial effects of color, texture, and depth. In Warrior, he arranged several abstract, cutout canvas shapes on a large canvas and emphasized these interlocking forms with touches of oil paint. The focus is the figure-like form at the center, an evolution from his single-figure compositions of the preceding years. Neutral colors, stability of forms, and his use of collage recall contemporary works by Italian artist Alberto Burri.

-

Kenzo Okada, Decision, 1956 591500

After Kenzo Okada relocated from Tokyo to New York in 1950, his work came to represent a melding of Japanese traditions and American abstract trends. Rather than striving for pure abstraction, he produced work starting in the 1950s that could be called semi-abstract, evoking the natural world through carefully composed form and a decidedly muted palette. These works are subtle, quiet, and poetic—more meditative in nature than the energetic gestural abstractions of some of his American-born counterparts. The composition of Decision is also organized to suggest natural topography. Blocky, softly defined shapes organically arrange the canvas into rough horizontal registers, creating a panoramic quality reminiscent of landscape painting. Meanwhile, small, irregular shapes hover and tumble rhythmically across the stable ground. Okada thus seeks a balance between heavy and delicate, tangible and abstract.

-

Judit Reigl, Outburst, 1956 595500

In 1955, five years after leaving Hungary for Paris, where she was briefly associated with André Breton's Surrealist group, Judit Reigl began a new series to explore the process of painting as a dynamic and corporeal activity. The resulting works, Outburst (1955–57), feature masses of exploded paint that traverse the surface of the canvas tracing the movements of the artist's body in action. This canvas, like each work in the rest of the series, was realized in a single session. Using a stretched canvas, which she tilted against a wall, Reigl worked by hurling a mixture of industrial pigment and linseed oil onto the surface by hand, adding paint with a long and flexible knife, then spreading and flattening it into diagonal bands with a bent curtain rod. Although Outburst shares some of the characteristics of the gestural and calligraphic tendencies of 1950s French abstraction, the vehement physicality of Reigl's practice suggests closer connections with the works of her American contemporaries, especially those of Willem de Kooning and Joan Mitchell.

-

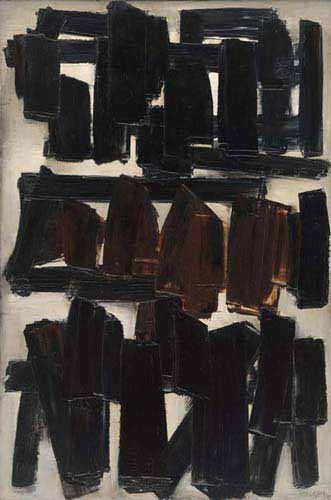

Pierre Soulages, Painting, November 20, 1956, 1956 331500

Pierre Soulages, a leading proponent of Tachisme (from the French word tache, meaning blot or stain), maintained that he had decided to become a painter while inside the church of Sainte-Foy in Conques-en-Rouergue, near his birthplace in the south of France. The impressions of monumentality, stability, primitive force, and clearly organized volumes characteristic of the Romanesque style, as well as the mystery and sobriety of dark church interiors, were metaphorically transmitted in his mature style. Throughout his career, Soulages painted in a predominately black palette to explore the contrasts of light and shade. In Painting, November 20, 1956, he divided the canvas into three horizontal registers, articulating each with a repetition of slablike black shapes that reveal a variety of red and brown nuances and a certain luminosity.

-

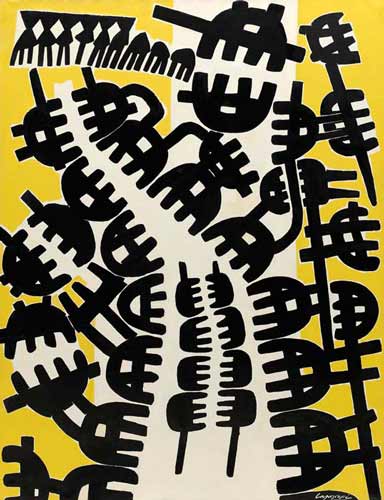

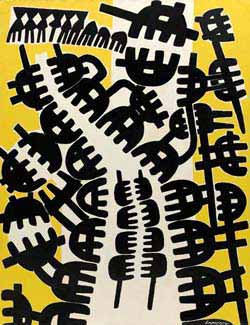

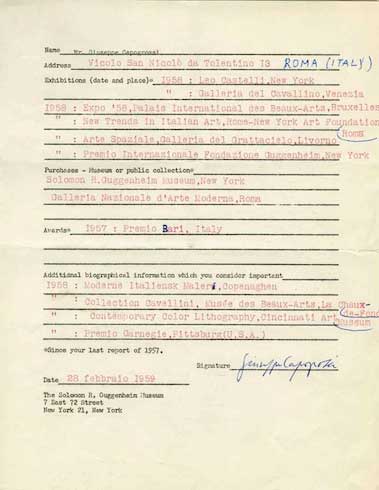

Giuseppe Capogrossi, Surface 210, 1957 384500 A decisive shift in Giuseppe Capogrossi's career took place in 1949, when he developed a vocabulary of irregular comb- or fork-shaped signs. With no allegorical, psychological, or symbolic meaning, these structural elements could be assembled and connected in countless variations. Intricate and insistent, Capogrossi's signs determined the construction of the pictorial surface. Similar to mysterious lists or sequences, his paintings were immediate in their appeal yet remained hard to decode, a quality he shared with the Informel artists. These abstract comb-sign paintings, known simply as Surfaces, were first exhibited at the Galleria del secolo, Rome, in 1950. The comb sign dominated his oeuvre until the end of his career.

A decisive shift in Giuseppe Capogrossi's career took place in 1949, when he developed a vocabulary of irregular comb- or fork-shaped signs. With no allegorical, psychological, or symbolic meaning, these structural elements could be assembled and connected in countless variations. Intricate and insistent, Capogrossi's signs determined the construction of the pictorial surface. Similar to mysterious lists or sequences, his paintings were immediate in their appeal yet remained hard to decode, a quality he shared with the Informel artists. These abstract comb-sign paintings, known simply as Surfaces, were first exhibited at the Galleria del secolo, Rome, in 1950. The comb sign dominated his oeuvre until the end of his career.

-

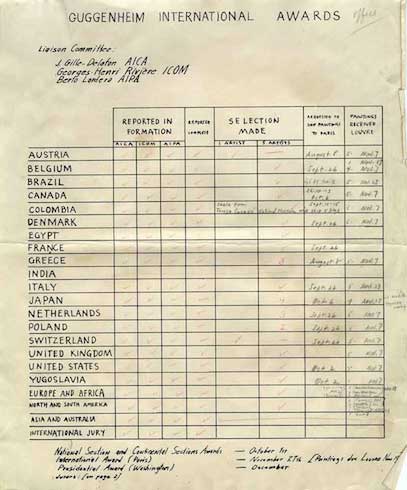

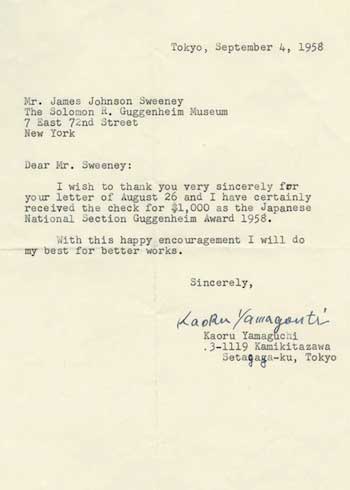

The Guggenheim International Awards and Exhibitions, 1956–71

In 1956, the Guggenheim Museum established the Guggenheim International Award (GIA) in order to foster support and garner international prestige for contemporary painters. The first three awards and accompanying exhibitions in 1956–57, 1958, and 1960 were presented with the cooperation of juries composed of artists, art critics, and directors from a range of international organizations. Bestowed on works that had been created up to three years prior to the award year, the awards ranged from $1,000 to a grand prize of $10,000. In 1967, the series was renamed the Guggenheim International Exhibition (GIE), with funds redirected toward acquiring artworks from the shows. The final GIE took place in 1971.

Giuseppe Capogrossi's Surface 210 (1957) was among the finalists on view at the 1958 GIA exhibition. Around 1949, the Italian artist had developed a unique vocabulary of irregular comb- or fork-shaped signs. With no allegorical, psychological, or symbolic meanings, these elements could be assembled and connected in countless variations. Intricate and insistent, Capogrossi's signs determined the construction of the pictorial surface. The Guggenheim acquired Surface 210 in 1958.

Giuseppe Capogrossi, Surface 210, 1957 Oil on canvas, 206.4 x 160 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 58.1518. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Oil on canvas, 206.4 x 160 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 58.1518. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

50content/video/InternationalAwardFinal_h264_Microsite.mp4images/art/International_posterframe.jpg475845

50content/video/InternationalAwardFinal_h264_Microsite.mp4images/art/International_posterframe.jpg475845

-

Grace Hartigan, Ireland, 1958 678500

Grace Hartigan's paintings were included in The New American Painting, an exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, that traveled to eight European cities from 1958 to 1959, making her one of the few women painters to receive that level of exposure. Hartigan, an artist of Irish descent, also visited Europe for the first time in 1958 and traveled extensively in Ireland. On her return to the United States, she painted a series of pictures with titles relating to Ireland, of which the present work is the largest. Though in no sense landscapes or pictures with any literal subject matter, they constitute for the artist abstract evocations of "place," and in that sense are deeply rooted in her experience of Ireland.

-

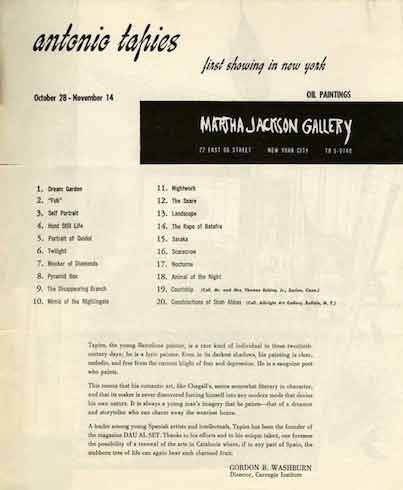

Antoni Tàpies, Great Painting, 1958 656500

Antoni Tàpies was among the artists to receive the label Tachiste (from the French word tache, meaning a blot or stain) because of the rich texture and pooled color that seemed to occur accidentally on his canvases. Many of his paintings resemble walls that have been scuffed and marred by human intervention and the passage of time. In Great Painting, violence is suggested by the gouge and puncture marks in the dense stratum. These markings recall the scribbling of graffiti, perhaps referring to the public walls covered with slogans and images of protest that the artist saw as a youth in Catalonia—a region in Spain that experienced harsh repression under dictator Francisco Franco. Great Painting suggests the artist's poetic memorial to those who have perished and those who have endured.

-

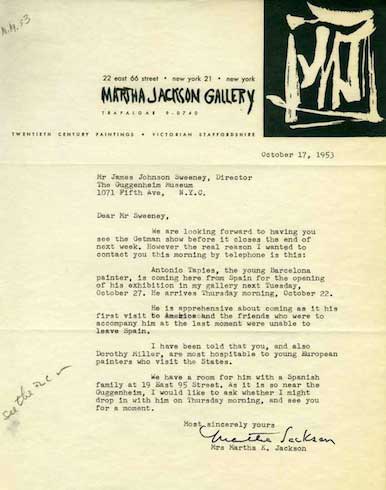

"Tastebreakers" of the 1950s

After his appointment as director of the Guggenheim Museum (formerly the Museum of Non-Objective Painting) in October 1952, James Johnson Sweeney considerably broadened the museum's scope through acquisitions and exhibitions of both modern and contemporary art. He championed what he called the "tastebreakers" of his day—those individuals who "break open and enlarge our artistic frontiers."

Spanish artist Antoni Tàpies was among the pioneers whose works were first added to the collection during Sweeney's directorship (1952–60). Many of Tàpies's works, including Great Painting (1958), resemble walls that have been scuffed and marred by human intervention and the passage of time. Sweeney likely encountered the artist in 1953, during Tàpies's first trip to the United States and through an introduction by New York art dealer Martha Jackson. He also served on the jury that awarded Tàpies a prize at the Pittsburgh International (now Carnegie International) in 1958. The Guggenheim acquired Great Painting from Jackson in 1959 and organized a major exhibition of the artist's work in 1962.

Antoni Tàpies, Great Painting, 1958 Oil with sand on canvas, 199.3 x 261.6 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 59.1551. © 2012 Fundació Antoni Tàpies/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VEGAP, Madrid

Oil with sand on canvas, 199.3 x 261.6 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 59.1551. © 2012 Fundació Antoni Tàpies/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VEGAP, Madrid

-

Asger Jorn, A Soul for Sale, 1958–59 636500

Asger Jorn was a founding member of Cobra, a European artists' group that emphasized material and its spontaneous application. Even after he formed the Situationist International in 1957—a Marxist, activist group of writers, artists, and theorists who sought to destabilize societal practices and structures—Jorn continued to work within his Cobra aesthetic, as seen in A Soul for Sale. In its use of expressive brushwork and its collapsing of foreground and background, figuration and abstraction, this painting articulates some of Jorn's most significant interrogations of the precepts of geometric abstraction and rationalized art making. Barely discernible amid a field of gestural marks, the work's central figure appears on the verge of disappearing. In a similar fashion, rational strategies of delineating form or representing depth, seen in the contour drawing or in the crosshatching at the top right of the painting, are overcome by strikingly crude or naive methods of mark making, such as scattered soil or paint smudges.

-

Takeo Yamaguchi, Work—Yellow, 1958 384385

In his native Japan, Takeo Yamaguchi was a pioneer of modern abstract painting. This focus led him to spend time in France, where he was much influenced by the work of Cubist practitioners in Paris until he returned to Japan in 1931. In the 1950s, Yamaguchi began executing works consisting of simple, geometric forms—largely yellow, ochre, or russet—painted on a black background. His thick pigments added texture to the monochromatic compositions, and, as seen in Work—Yellow, his abstract shapes increasingly dominated the canvas. This painting was prominently displayed on the ground floor of the Guggenheim's rotunda during the 1959 exhibition that inaugurated the museum's Frank Lloyd Wright–designed building, attesting to then-director James Johnson Sweeney's keen interest in Yamaguchi's work.

-

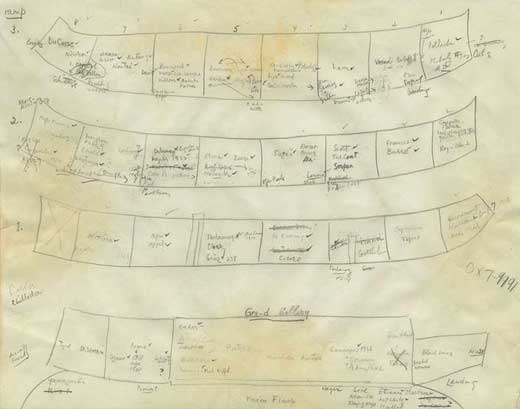

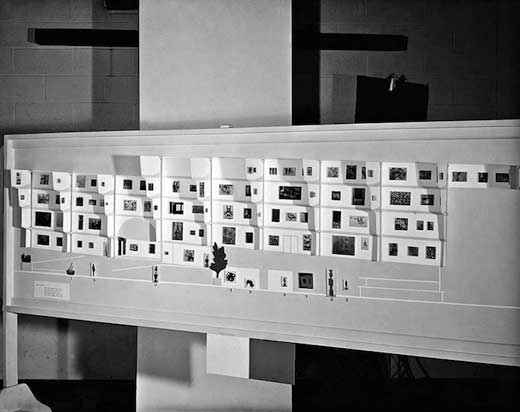

Contemporary Acquisitions on Display in 1959

When the Guggenheim Museum opened its Frank Lloyd Wright building in 1959, then-director James Johnson Sweeney curated the inaugural exhibition featuring more than 120 works from the collection. Besides including art by Vasily Kandinsky and other modernists collected by Solomon Guggenheim and his wife Irene, the opening showcased 69 acquisitions under Sweeney's directorship (1952–60). With 40 examples of painting and sculpture from the 1950s, the exhibition emphasized Sweeney's commitment to the contemporary avant-garde in the tradition of the founders.

Acquired in 1958, Takeo Yamaguchi's Work—Yellow (1958) was prominently displayed in the rotunda during this inaugural show. A Japanese painter engaged with European Informalism and explorations of the monochrome, Yamaguchi was selected to represent Japan at the Guggenheim International Award, 1958 exhibition (1958–59). Work—Yellow was first exhibited in the accompanying award presentation at the museum's temporary location. During Sweeney's directorship, significant acquisitions of work by Asian American and Asian artists, whom he found a "fresh influence" on American abstract practitioners, were introduced to the collection.

Takeo Yamaguchi, Work—Yellow, 1958 Oil on plywood, 182.6 x 182.6 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 59.1529. © Takeo Yamaguchi

Oil on plywood, 182.6 x 182.6 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 59.1529. © Takeo Yamaguchi

73content/video/InauguralExhibitFinal_h264_Microsite.mp4images/art/Inaugural_posterframe.jpg475845

73content/video/InauguralExhibitFinal_h264_Microsite.mp4images/art/Inaugural_posterframe.jpg475845

-

Jean Dubuffet, The Substance of Stars, December 1959 653500

In Jean Dubuffet's Matériologies series (1959–60), of which The Substance of Stars is an example, form is subverted by an emphasis on materials, meant to stimulate mental responses and associations in the viewer. Far from being an abstraction in the usual sense, this and other such works suggest a concern with topographical reality—the earth, water and sky, and the stars. These elements are conveyed not through descriptive images or the use of materials identical with a natural substance but through the evocative effects of their artificial counterparts—here, black, gray, and silver metal foil. Nature, although closely observed, is thus rendered through artifice, and reality conjured up through elaborate illusion.

-

75content/video/ExhibitionVideoFinal_H.264_1280x720.mp4images/art/exhibitionvideo_posterframe.jpg475845

-

The Leadership Committee for Art of Another Kind: International Abstraction and the Guggenheim, 1949–1960 is gratefully acknowledged for its support.