Over a career that spans three decades, Christopher Wool has conducted a riveting investigation into the question of how to make a painting at a time when new possibilities for the medium might seem exhausted. Extending his practice to photographs, prints, artist’s books, and, most recently, sculpture, he has approached each new work as a site of open-ended experimentation in which images exist as volatile entities that are subject to an array of disruptive processes.

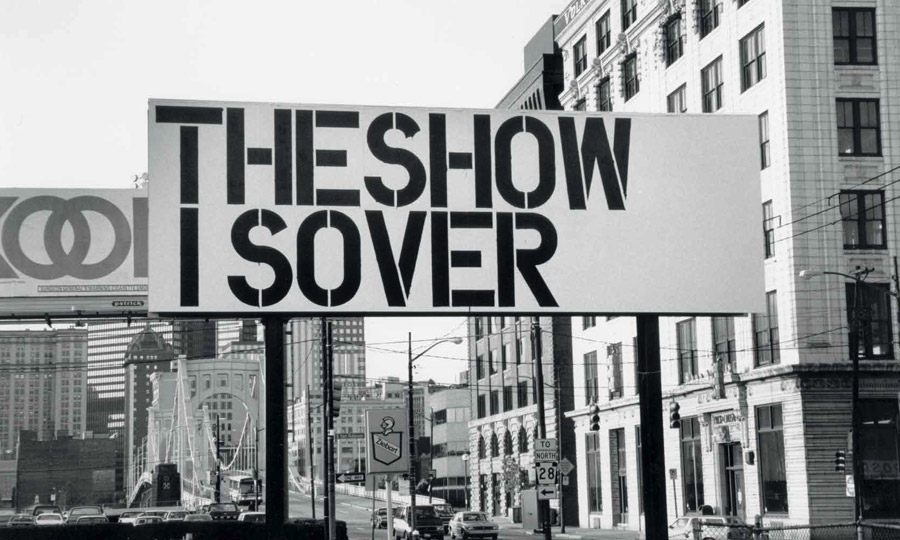

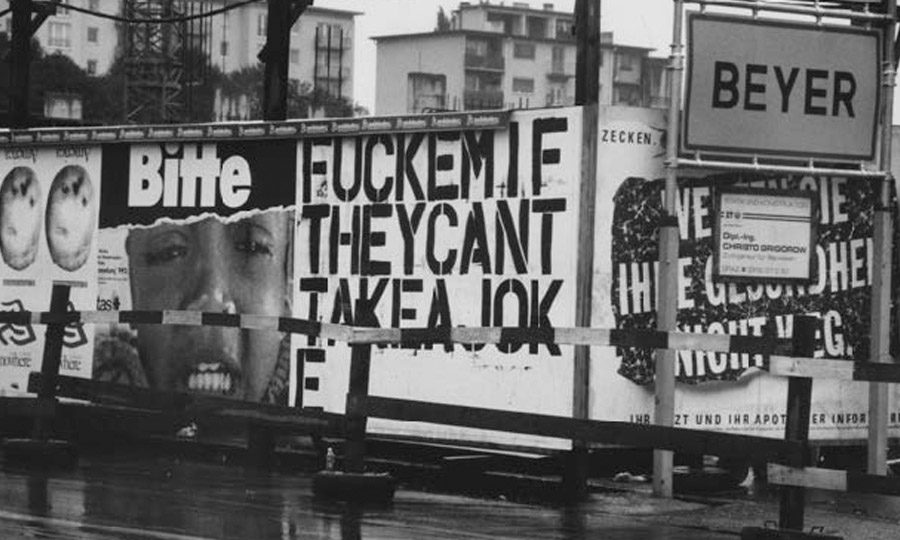

Wool was born in 1955 and grew up in Chicago. By the time that he turned eighteen he had moved to downtown New York City, where the anarchic energy of the punk and No Wave scenes were a defining influence on his creative development. At the outset of his mature career in the mid-1980s, Wool abstained from the seductive expressionism of color and the gestural brushstroke in favor of stark, monochrome compositions that employed commercial tools and imagery appropriated from mass culture. His breakthrough body of work used rollers and stamps to transfer decorative patterns in severe black enamel to a white ground. His “word paintings” from the same period focused on language as image, confronting the viewer with anxious, enigmatic imperatives even as the stenciled letters disintegrate into abstract geometries. In both cases, Wool used unexpected breakdowns in his formal systems—slips and glitches, fractured text and erratic spacing—to convey emotional states ranging from pathos to aggression.

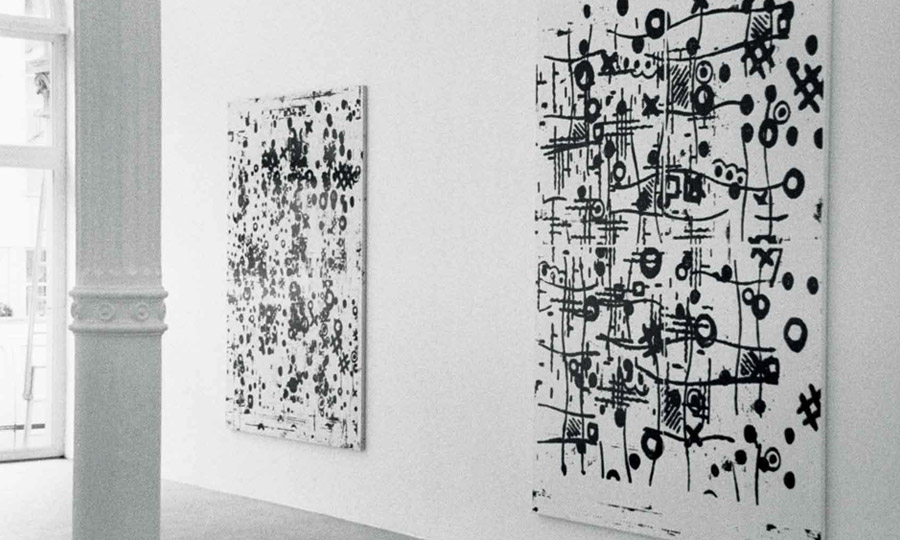

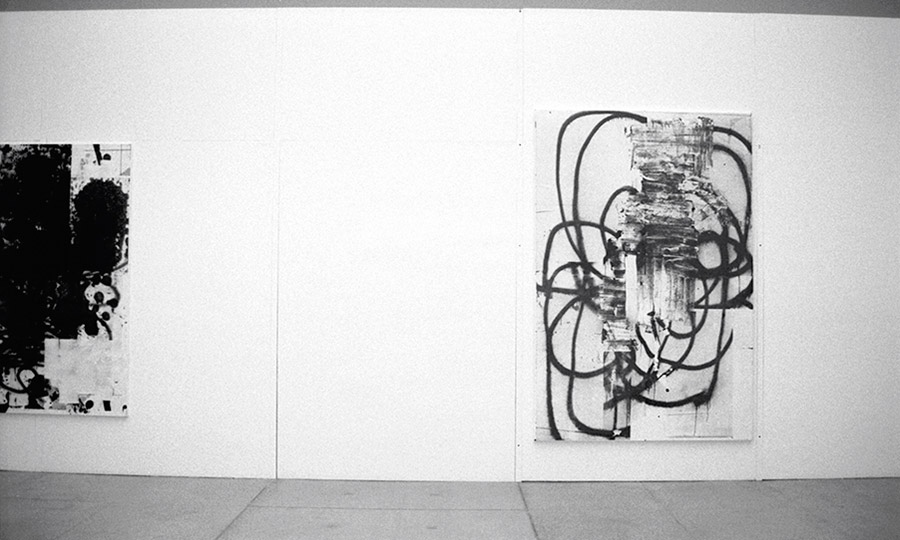

The same tension between control and disorder runs through Wool’s work of the 1990s, when he adopted the silkscreen as a primary tool. Cartoonish flowers began to multiply in dense configurations across his paintings, at times interrupted by irreverent passages of overpainting or scribbles of spray-paint that evoke an act of vandalism on a city street. Wool’s practice has always had a porous relationship with the world outside the studio, channeling an abrasive urban vernacular. The scenes of alienation and decay collected in his photographic series make this connection explicit, their fugitive compositions resonating with the vocabulary of his paintings.

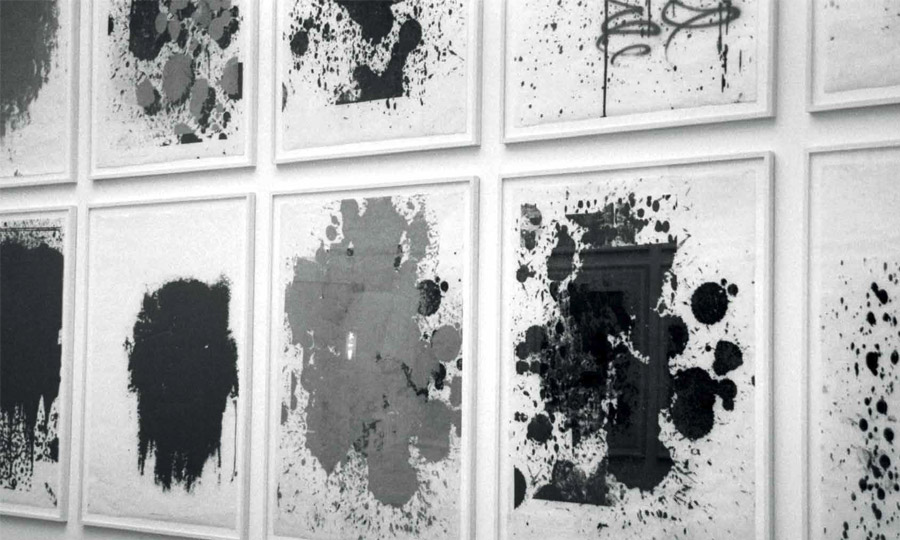

Since the early 2000s, Wool has worked almost entirely with abstract forms, at once mediating and renewing the expressive potential of painting through strategies of replication, erasure, and digital manipulation. His large-scale “gray paintings” emerge from a cycle of addition and subtraction, as tangles of black lines are repeatedly wiped into fields of hazy washes. The authority of the artist’s hand is similarly challenged when he reworks images of his own finished paintings, coolly considering them in digital form before screenprinting them to new canvases, either as deadpan reiterations or as ghostly traces collaged with other elements. For Wool, these acts of sabotage and self-negation express the position of doubt and insistent questioning that has underpinned his work from the beginning, and that continues to drive him forward in search of new ways to create a picture.