Biography

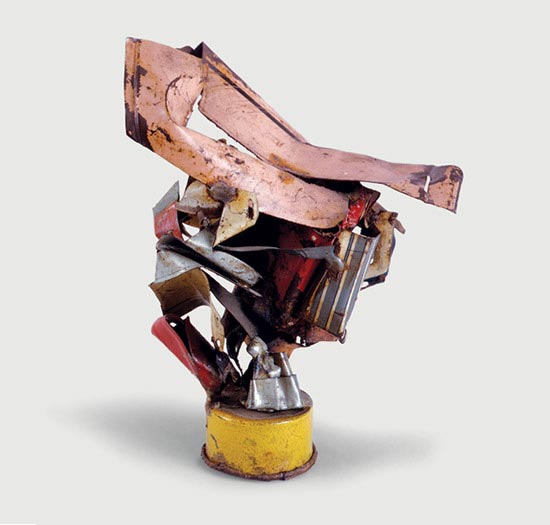

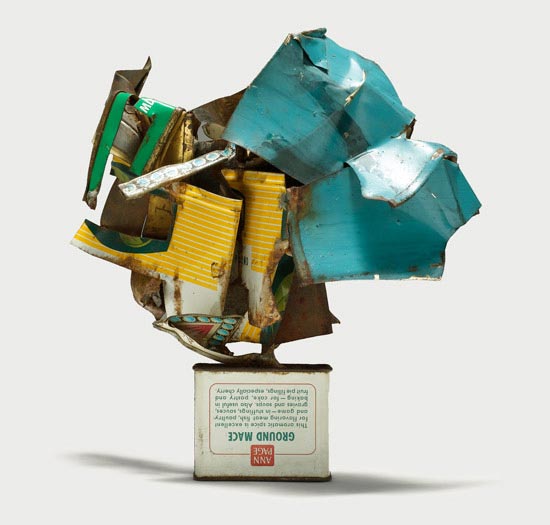

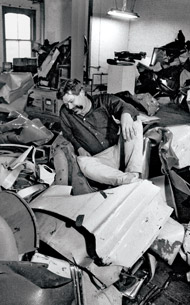

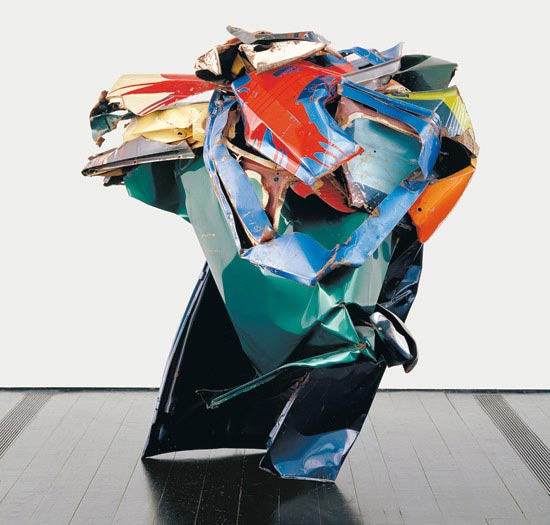

John Chamberlain was born in 1927 in Rochester, Indiana. He grew up in Chicago and, after serving in the navy from 1943 to 1946, attended the Art Institute of Chicago from 1951 to 1952. At that time, he began making flat, welded sculptures influenced by the work of David Smith. In 1955 and 1956, Chamberlain studied and taught sculpture at Black Mountain College, near Asheville, North Carolina, where most of his friends were poets, including Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, and Charles Olson. By 1957, he began to include scrap metal from cars in his work, and from 1959 onward he concentrated on sculpture built entirely of crushed automobile parts welded together. Chamberlain’s first major solo show was held at the Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, in 1960.

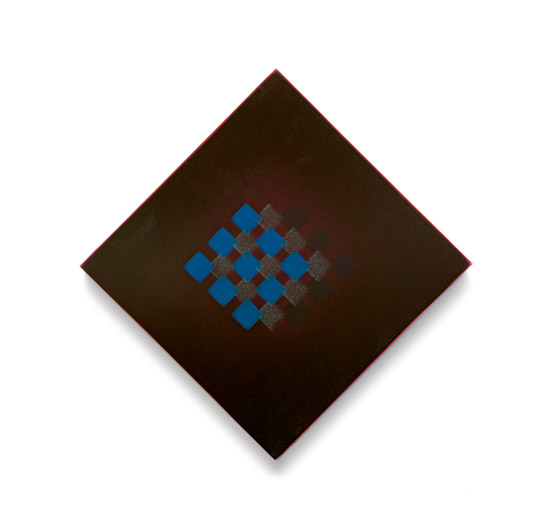

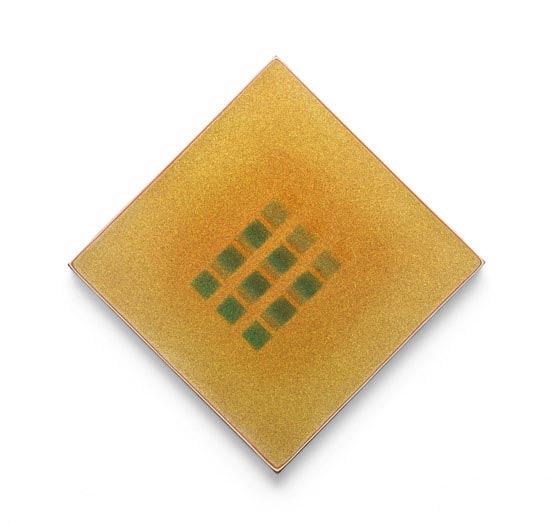

Chamberlain’s work was widely acclaimed in the early 1960s. His sculpture was included in The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1961, the same year he participated in the São Paulo Biennial. From 1962, Chamberlain showed frequently at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, and in 1964 his work was exhibited at the Venice Biennale. While he continued to make sculpture from auto parts, Chamberlain also experimented with other mediums. From 1963 to 1965, he made geometric paintings with sprayed automobile paint. In 1966, the same year he received the first of two fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, he began a series of sculptures of rolled, folded, and tied urethane foam. These were followed in 1970 by sculptures of melted or crushed metal and heat-crumpled Plexiglas. Chamberlain’s work was presented in a retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1971.

In the early 1970s, Chamberlain began once more to make large works from automobile parts. Until the mid-1970s, the artist assembled these auto sculptures on the ranch of collector Stanley Marsh in Amarillo, Texas. These works were shown in the sculpture garden at the Dag Hammarskold Plaza, New York, in 1973, and at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, in 1975. In 1977, Chamberlain began experimenting with photography taken with a panoramic Widelux camera. His next major retrospective was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 1986; the museum simultaneously co-published John Chamberlain: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Sculpture 1954–1985, authored by Julie Sylvester. In 1993, Chamberlain received both the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture and the Lifetime Achievement Award in Contemporary Sculpture from the International Sculpture Center, Washington, D.C. In 1997, Chamberlain was named a recipient of The National Arts Club Award, New York, and in 1999, received the Distinction in Sculpture Honor from the Sculpture Center, New York. In the last decade of his life, the artist expanded his well-established career by undertaking a new medium: the large-format photograph. In 2007, Guild Hall Academy of the Fine Arts named Chamberlain the Visual Arts Honoree for the 22nd Annual Lifetime Achievement Award. Chamberlain passed away on December 21, 2011 in New York.

Sculpture as Collage

Sculpture as Collage

Choices

Choices